A St. Jude mother's resolve: 'She is not going to die.'

It has been 20 years since Mariangeles Grear was cured of childhood cancer. It was her mother's voice that carried her through.

March 29, 2021 • 7 min

English | Español

Mariangeles Grear was 13 years old, lying in a hospital bed at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital so near death there was a chance she might not wake from a coma.

It wasn’t the acute myeloid leukemia that was killing her at the moment. It was an infection doctors couldn’t find. It may have reached her brain, they said. And no medication was working to stop it.

Mariangela Rubio, Mariangeles’ mother, refused to let her daughter surrender.

Mi amor, she said. Despierta. Regresa a mí.

My love. Wake up. Come back to me.

She prayed the rosary and asked God and the Virgin Mary to heal her daughter.

She’s ashamed of how much she cried in those days. But she never wavered over whether her daughter would live. Not once.

“I believe in the Lord and St. Jude,” Mariangela said. “Every problem has a solution.”

This year marks 20 years since Mariangeles was cured of AML, a type of blood and bone marrow cancer. And it’s been her mother’s voice – uncompromising, unwavering, unrelenting – that has seen her through all those years. The cancer. Two hip replacements. And now infertility.

“My mom is my rock through everything in life,” Mariangeles said. “She is the reason I could look cancer in the face: I’m not scared of you because you should be scared of my mom.

A deadly diagnosis

“If you think you’re coming for me, you better think twice because of that red lipstick over there.”

It was September 2000 in Maracaibo, Venezuela, when Mariangeles fell ill with a mysterious sickness. Her gums were so swollen her teeth seemed to disappear. Purple and yellow bruises covered her body. And her fever was, at times, so high that even her eyelids burned.

Her pain was in both flesh and bone.

“I have no power in my body,” she told her mother.

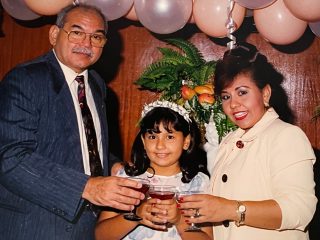

Mariangeles Grear poses with her parents at her First Communion party in Venezuela.

It was the only way she could describe how she felt.

Even Mariangeles’ father, a doctor, didn’t know what was wrong with their daughter.

After many tests, a hematologist at a private hospital delivered devastating news: Mariangeles had advanced cancer and needed an immediate bone marrow transplant. And that wasn’t possible in Venezuela.

Without one, the doctor said, she might only have five days to live.

Mariangeles’ father wept.

As a doctor, he knew her condition was grave. He was resigned to find Mariangeles a comfortable room in the clinic to spend her last days.

But Mariangeles’ mother was defiant. She demanded to see the paperwork.

“Who are you to tell me my daughter will die in five days?” she told the doctor. “She is not going to die.”

The doctor suggested the family travel to Italy or Cuba. Maybe the United States.

There was this place in Memphis called St. Jude. The doctor would refer her to see if she could be treated there.

Mariangela had been a high-ranking official under former Venezuelan President Rafael Caldera. She’d traveled the world – to Italy, Colombia, the United States. But always to New York or Miami.

Hope in the patron saint of lost causes

The only thing she knew about Memphis: It was the city where Elvis was from.

In a matter of days, Mariangeles and her parents arrived in Memphis, before the marble statue of St. Jude Thaddeus at the entrance of the hospital. Patrón de las causas perdidas, her mother thought. The patron saint of lost causes.

“Mi amor, my love – this hospital – you’re going to have no more problems here,” she said.

Mariangeles didn’t need a bone marrow transplant after all, only chemotherapy.

But the next nine days would prove to be the most tormenting of her mother’s life.

The chemo Mariangeles was given the first day was working. But the fungal infection would not abate. Mariangeles’ lungs were filling with fluid. Doctors induced a coma. She was put on a ventilator.

Mariangela never left the room.

In the haze of the coma, Mariangeles recognized the sound of the automatic doors— fooffhh — the yellow protective gear that turned nurses into astronauts, and her mother’s ever-present voice. Pleading for her to be strong, to come back.

Creer en San Judas. Creer en el Señor. Creer en ti mismo.

Believe in St. Jude. Believe in the Lord. Believe in yourself.

Doctors offered to try a new medicine, and Mariangeles’ parents agreed. It worked. But even as the doctors weaned her from the induced coma, she did not wake up.

Still, her mother refused to give in. Her daughter would not die.

She kept talking. Praying the rosary. Calling Mariangeles’ name.

On the ninth day, Mariangeles called out — garbled — over the tube in her mouth:

Mami?

The first face she saw was her mother’s — coal black hair perched in an updo and her signature red lipstick, Velvet No. 37.

Fighting for health, searching for beauty

The only way to explain it, Mariangela said, was that her daughter was a miracle.

For the next six months, Mariangeles endured five rounds of chemo. She lost weight. Her skin turned dark. And she threw up almost every day.

“If you can just go to sleep and die, it will stop,” Mariangeles remembered thinking. “That’s why people give up. The pain is indescribable.”

But her mother told her to eat when she didn’t feel like it. Said to hold on when things got hard. Told her to believe God had a mission for her life.

Even when Mariangeles woke to clumps of hair on her pillow — once long and full like the Miss Venezuela contestants she so admired — her mother did not abide sulking. The hair would grow back.

In the meantime, they’d buy dangly earrings, pink caps — and lipstick.

“She was saying: ‘We can make you beautiful without hair,’” Mariangeles said.

Mariangeles Grear poses in a red hat while on a fanciful St. Jude excursion to the North Pole.

Every problem has a solution.

Mariangeles' dad had to go back to Venezuela four months into her treatment — to his medical clinic and to Mariangeles' other siblings. But her mother never left her side.

And just six days before her 14th birthday, Mariangeles was declared cancer free.

A life to live, a dream to catch

“Everything I went through, she was there.”

After treatment, Mariangeles’ mother got a government job in Memphis so she stayed in the United States. Mariangeles went back to Venezuela for a year with her dad but came back to St. Jude every three months for check-ups. When she developed a polyp in her nose, her mother decided Mariangeles needed to be close to the hospital, in case anything else went wrong.

So Mariangeles moved to Memphis for good.

She grew her hair out again and didn’t cut it for five years. Long, thick locks tumbled down her back again, just like the Miss Venezuela contestants.

She graduated high school, then college and went on to work in national, big-name firms in business development. She was grateful to St. Jude for saving her life but wanted to put cancer behind her. She didn’t tell people she was a cancer survivor, never brought it up in job interviews or in meet-ups with new friends. She kept that part of her story to herself.

She was reluctant to tell even her now-husband, Matthew Grear, for fear he might pity her.

It wasn’t until 2017 when she joined ALSAC, the fundraising and awareness organization for St. Jude, as a development specialist that she started to feel comfortable telling her own story.

Long before she spoke publicly, she had been part of St. Jude LIFE, a research study that brings former cancer patients back to campus for regular health screenings.

Devastating news

Now, that decision may well shape her dream to come.

In April 2019, Mariangeles was in the Dallas airport, waiting for a connecting flight when she got a call from her OB-GYN with some distressing news: Tests showed she was pre-menopausal and had the eggs of an older woman.

Mariangeles was only 31.

There was no way to know why this was happening. Many factors affect fertility. But there was no time to waste. The OB-GYN had already made her an appointment with a prominent fertility specialist in Memphis. But that was four months away.

Mariangeles wept.

The young girl who had collected dolls, the one who treated her siblings as if they were her own children might not be able to have a baby of her own.

“We always have this joke: We’re Catholic. It’s in the wine,” Mariangeles said.

But what if that was not to be?

Mariangeles called her mother, inconsolable about the heartache that might come.

The voice on the other end of the line was having none of it.

“Did she tell you that you couldn’t have kids?”

No.

“Then wait until they tell you that.”

Mariangeles and her husband, Matthew, pose in front of the statue of St. Jude Thaddeus on campus.

Every problem has a solution.

That week, Mariangeles was at her St. Jude LIFE appointment when she broke down, sobbing. She told the nurses and her social worker about the fertility test results.

Two days later she was referred to the St. Jude fertility clinic for a consultation with doctors.

“Come to find out, God had a bigger plan,” Mariangeles said.

The doctor who walked in was the same specialist her OB-GYN said would take four months to see.

How about the following Monday? Could her husband come to see him then?

Yes. It was her birthday.

Since then, Mariangeles has gone through three rounds of artificial insemination, which were unsuccessful.

But in February, she began hormone treatments at a private fertility clinic for in vitro fertilization — thanks to the consulting doctor who’s known as a leading fertility specialist in Memphis.

All because of St. Jude.

"Three years ago I was crying in an airport because … I was not gonna be able to have a kid,” Mariangeles said. “And today I sit back and reflect how St. Jude has, once again, given me that hope. They connected me to the doctor. They got me into the best doctor in Memphis.”

For Mariangeles, the dream of a family seems so close.

“I know I can’t get ahead, but I close my eyes and see myself at that first (ultrasound) when you can hear the heartbeat,” she said. “Or if it’s a daughter, going to buy all the bows that I can find in the world.

“She will be my real-life baby doll. I will play dress up with her. And if it’s a boy, let’s go get a bat because you’re going to be the next baseball player because that’s what my dad did.”

But then she hears her mother’s voice. There is no doubt.

“Mariangeles will have a baby this year,” her mother said. “Believe me.”

Every problem has a solution.