LIKE TEST - article page

July 06, 2021 • 4 min

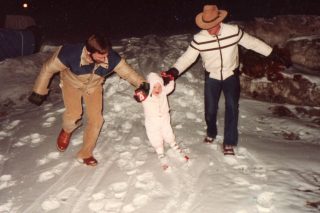

DENVER, Colorado — In the photo, Jessie Wagner is about 2 years old and standing on the snow in a pair of plastic skis, supported on one side by her dad and on the other by her uncle. They’re in Colorado, where the family often vacationed, and where Jessie, now grown, has lived for years.

By age 3, Jessie was skiing on her own. As kids, she and her brother decided they'd be the first brother-sister duo to compete in the Olympics. It wasn’t idle daydreaming: He went on to be a Junior Olympian.

There’s a technique in skiing called slaloming. It means to ski in a winding path, avoiding obstacles. When Jessie was 16, an accomplished four-season athlete and competitive ski racer, her life threw up a major obstacle — one that could not be gone around, only through. She was diagnosed with cancer.

It wasn’t the first time.

Not only was little Jessie learning to ski at the age some kids learn to walk, she was, at the time, not long out of treatment for Wilms tumor, a form of kidney cancer discovered when she was 6 months old. She underwent surgery and six months of chemotherapy at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. At one of her checkups, when she was still very small, a St. Jude social worker told her mom, “She’s going to want to help people, I can just tell; It’s in her spirit.”

But as she got older, competitive sports were calling — volleyball, basketball, softball and the slopes. Jessie could have gone pro as a ski racer. Then came that second, unrelated cancer diagnosis: thyroid cancer.

At 16, Jessie returned to St. Jude. She had surgery to remove her thyroid and then radioactive ablation treatment, at a partnering hospital near St. Jude.

“I swallowed a pill, and I became radioactive,” she explained. “Radioactive iodine actually attaches to thyroid cells both good and bad and destroys them. I had lead shields around my bed, and everything was plastic-wrapped because radiation attaches to plastic and porcelain. And I basically just had to stay in that room until my radiation levels came down. My mom couldn't come in the room at all, and anything that went into the room with me couldn't come out, so I couldn't take my stuffed lion that had gone through the entire experience with me.

"All I brought in was my underwear and a photocopied picture of my boyfriend at the time. So it was a very isolating experience. It was not easy for me at 16. And then I did it again about a year and a half later.”

Now came a choice in executing the slalom. Would she turn back toward skiing or veer toward her studies in order to graduate on time? She chose the latter. And this is when that social worker’s prediction really began to manifest.

Still not quite out of the woods in terms of the thyroid cancer, Jessie began studying science as an undergrad. She was accepted to a research internship through the St. Jude Pediatric Oncology Education Program, returning by choice to the hospital where she had twice been a patient.

She was deeply involved in fundraising for St. Jude at her college in Michigan, and then moved to Philadelphia with the non-profit organization Teach For America, where she taught science at an under-resourced, inner city school.

She earned a Master’s degree in education and now designs medical education programs for surgeons and operating room staff. It’s not lost on her that surgeons played a role in saving her life, twice. What she loves about her work now is making the surgical experience better for “the patient, the surgeon, the nurse, the scrub tech” — in short, everyone she can.

“Medical education for me is a tie to giving back,” she said. If she can help train medical residents on a piece of technology that will help them remove a tumor more completely or less invasively, she is ultimately helping patients achieve better outcomes.

While teaching in Philadelphia, Jessie revitalized a senior mentor program to help students nearing graduation determine what they wanted to do for their next step.

“I love those periods of transition,” she reflected. “Those are, for me, really cool places to be able to support and guide and coach others. I think those periods of transition are where we grow the most. Those can be some of the richest times in our lives.”

Jessie has negotiated her own transitions, some tough, some freeing, but ultimately, she has stayed her true course. You can see in her trajectory the through-line of a personal mission to be of service.

“I think my cancer experience has certainly given me this feeling that I want to make a difference in this world. I feel lucky and blessed to be here. St Jude helped me not once, but twice, and so, for me, part of what I want my legacy to be about is giving back.”

And in her downtime, Jessie still get outside of Denver, and skis.