St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Policy Report

Updated Analysis of Public Policy Decisions and Factors Driving HPV Vaccination Coverage in the United States, 2023

Every year, millions of individuals in the United States (U.S.) are exposed to human papillomavirus (HPV), a virus that is linked to six different types of cancer that can affect anyone. Approximately 13 million Americans will become infected with HPV each year, and more than 37,000 individuals will develop HPV cancers.1,2 Fortunately, there is a vaccine available that is safe, effective, and proven to help prevent more than 90% of the cancers caused by HPV.3 However, too many vaccine-eligible individuals are not getting vaccinated as recommended. As a result, a diverse group of partners, providers, advocates, policymakers, and interest groups have been seeking innovative policy solutions to increase HPV vaccination coverage. Increasing HPV vaccination coverage will reduce HPV cancer incidence and mortality and will contribute significantly to eliminating HPV cancers.

Through activities focused on clinical interventions, community interventions, and public policy and advocacy efforts, the HPV Cancer Prevention Program at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital strives to galvanize existing successful efforts and to introduce new ones to support increasing HPV vaccination coverage in the U.S. St. Jude partnered with FTI Consulting to examine public policy decisions and related factors that drive HPV vaccination coverage across the U.S. Ultimately, the research and analysis conducted by FTI Consulting are intended to educate and inform allies, partners, and advocates about public policy strategies, approaches, and opportunities that might have a meaningful impact on national, state, and local efforts to increase HPV vaccination coverage.

Factors Examined

The research and analysis conducted by FTI Consulting examined the relation between HPV vaccination initiation and series completion with regard to nine factors:

- Medicaid income eligibility for children

- Insurance coverage

- Parents' educational level

- Access to pediatricians and primary care physicians

- Access to Vaccines for Children (VFC) providers

- Coverage of other adolescent vaccinations

- Vaccination exemptions

- Vaccination requirements

- Rurality (i.e., the percentage of the population living in rural geographic regions of the U.S.)

Policy Recommendations

The analysis revealed factors with a positive relationship to HPV vaccination that may be leveraged to increase HPV vaccination coverage. Conversely, existing and new policies and regulations could help address factors that have a negative impact on HPV vaccination coverage. Using the results of the analysis, FTI Consulting developed five policy recommendations to improve HPV vaccination coverage:

- Leverage meningococcal conjugate vaccination as a model for HPV vaccination education and recommendations.

- Expand health care provider and practice staff education and training related to HPV vaccination and strengthen HPV vaccination recommendations for parents and caregivers.

- Improve recruitment efforts to enroll various health care provider types at the state level in the federal Vaccines for Children (VFC) program.

- Expand the resources available to improve HPV vaccination data collection and reporting through state immunization information systems (IISs)

- Engage in efforts to preserve and expand eligibility for Medicaid.

Cost Savings Analysis

FTI Consulting also conducted a cost savings analysis. This analysis projects that the increased HPV vaccination series initiation and reduced HPV cancer incidence that would result from addressing these policy factors could reduce the two-year national direct health care expenditures by nearly $19 million. In addition, the increased HPV vaccination series completion and reduced HPV cancer incidence could reduce the two-year national direct health care expenditures by more than $24 million. It's crucial to emphasize that the cost savings analysis undertaken in this study adopts a conservative approach, concentrating exclusively on the two-year cancer treatment costs linked to the HPV vaccine.

The increased HPV vaccination series completion and reduced HPV cancer incidence that would result from addressing these policy factors could reduce national direct health care expenditures by more than $24 million.

Benefits of HPV Cancer Prevention through Policy Change

Implementing these new policies requires investment and participation by multiple partners across sectors at the national, regional, state, local, and system levels. Therefore, allies must prioritize collaboration to increase HPV vaccination coverage. Partners must work together to develop consistent and effective HPV cancer prevention messaging, educational tools, and resources that consider the differing needs of communities and of the individuals and families within these communities. In addition, partners should be prepared to communicate the value of HPV vaccination to policymakers and health care experts who can provide the funds, coordination, and staffing needed to support, expand, and initiate the policy recommendations detailed in this report.

Methods

FTI Consulting performed quantitative research and analysis in the form of multivariate regression analyses, testing the relation between HPV vaccination initiation and completion with regard to nine key factors that affect HPV vaccination coverage: (1) Medicaid income eligibility for children (as a percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL); (2) parental education (college or above); (3) access to pediatricians and primary care physicians (nationally and in rural areas); (4) access to VFC providers (nationally and in rural areas); (5) commercial and public insurance status of children; (6) other childhood vaccination coverage (meningococcal vaccine and Tdap); (7) vaccination exemptions; (8) vaccination requirements; and (9) rural areas (i.e., the percentage of the population living in rural areas). To perform the analysis, FTI Consulting used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) and Decennial Census of Population and Housing, County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHR&R), the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES-ED), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), KFF, and the American Board of Pediatrics.

FTI Consulting also performed a cost savings analysis to estimate the direct medical cost savings that would potentially result from increased HPV vaccination initiation and series completion and the subsequent reduced incidence of HPV cancer. Using CDC data and peer-reviewed literature,3,4 FTI Consulting applied information on cancer treatment costs, HPV cancer cases, and the effectiveness of available HPV vaccines to the regression model results to estimate the cost savings that would result from increased HPV vaccination initiation and series completion and the subsequent reduced incidence of cancer.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 For treatment costs, average direct medical expenses during the first two years after diagnosis were used in the model. Direct medical prices include those for medical care services, such as physician services, diagnostic tests, and hospitalization expenses. Cost savings were calculated for four actionable policy factors:

- Average meningococcal conjugate vaccination coverage

- Medicaid eligibility expansion

- Access to VFC providers

- Access to pediatricians

The estimates consider direct medical costs during only the first two years after the diagnosis of HPV cancer. The net cost savings over the lifetimes of these patients will be much more substantial. The study was unable to characterize pre-cancers of the cervix and other HPV diseases for this analysis.

The quantitative analysis was complemented by qualitative research, including two focus groups and five one-on-one interviews with people who identified as providers, public health experts, patient advocates, and/or cancer prevention and control researchers. The results of both the quantitative and qualitative analysis were used to inform policy insights and recommendations related to the observed factors.

Policy Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Leverage meningococcal conjugate vaccination as a model for HPV vaccination education and recommendations.

A 1% increase in meningococcal conjugate vaccination coverage is associated with more than $15 million in savings by avoiding medical expenses that are typically incurred during the first two years after an HPV cancer diagnosis as a result of increased HPV vaccination series completion and, therefore, a reduced incidence of HPV cancer.

Coverage for meningococcal conjugate vaccination, which, like HPV vaccination, is recommended for children starting at 11 years of age but is not consistently required for school entry nationwide, had the strongest positive relation with HPV vaccination initiation and series completion in the regression analysis. Additional research shows that adolescents who receive at least one other childhood vaccine are more likely than their counterparts to initiate HPV vaccination, indicating that meningococcal conjugate vaccination could be leveraged as a critical factor in influencing HPV vaccination coverage.12

The cost savings analysis by FTI Consulting found that a 1% increase in meningococcal conjugate vaccination coverage is associated with nearly $13 million in savings by avoiding medical expenses that are typically incurred during the first two years after an HPV cancer diagnosis as a result of increased HPV vaccination series initiation and, therefore, a reduced incidence of HPV cancer. A 1% increase in meningococcal conjugate vaccination coverage is also associated with more than $15 million in savings by avoiding medical expenses that are typically incurred during the first two years after an HPV cancer diagnosis as a result of increased HPV vaccination series completion and, therefore, a reduced incidence of HPV cancer.

Policies should encourage training health care providers to recommend HPV vaccination as strongly as they recommend the meningococcal conjugate vaccine. Additionally, health systems and payors should establish a plan to educate and incentivize providers who have a large gap between HPV vaccination and meningococcal conjugate vaccination rates.

Recommendation 2: Expand health care provider and practice staff education and training related to HPV vaccination and strengthen HPV vaccination recommendations for parents and caregivers

In the analysis, parents with a college education had the second-highest positive impact on HPV vaccination initiation and series completion. Although cancer prevention partners and advocates may not be positioned to affect the education level of parents and caregivers, there are other ways to increase knowledge of HPV vaccination. Qualitative research participants said that the decision of parents or caregivers – those who make vaccination decisions in a family – to vaccinate their children largely depends on a recommendation from their children’s health care provider. Providers are vital to facilitating vaccination, but focus groups and interview participants indicated that providers receive inconsistent messaging about HPV vaccination and cancer prevention from national public health, vaccination, and cancer control leaders, which affects their vaccine recommendations and practices. Research participants emphasized the need for consistent messaging from organizations and leaders at the national and local levels that HPV vaccination is a cancer prevention measure.

Broadening the reach and dissemination of existing training and educational programs and leveraging cancer specialists and oncologists as messengers could improve providers’ understanding of the HPV vaccine as a cancer prevention vaccine. These training and education programs also empower providers and practice staff to better address educational gaps among parents, caregivers, and patients that influence uptake of preventive care. This training should extend across health systems and practices to ensure that patients, parents, and caregivers receive consistent messaging at every touchpoint in the health care provider’s office when seeking care. In addition, emphasis should be placed on provider and practice training to initiate the vaccination series as a cancer prevention method at 9 years of age to ensure series completion by 13 years of age. This approach will also combat parental and caregiver hesitancy surrounding the administration of multiple vaccinations recommended during the well-child visit at 11 years of age and will increase the likelihood of the child being vaccinated before exposure to HPV, which is when the vaccine is most effective.

Recommendation 3: Improve efforts to recruit various types of health care providers at the state level and enroll them in the federal Vaccines for Children (VFC) program

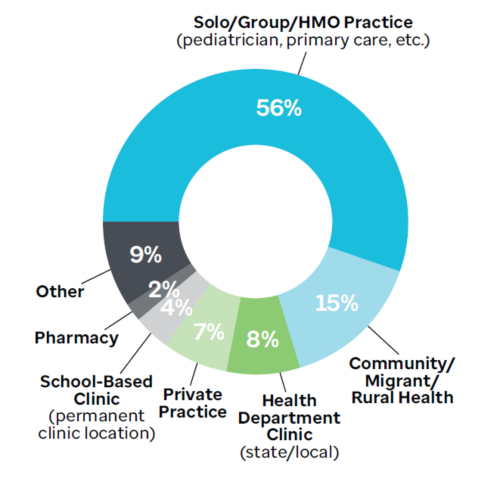

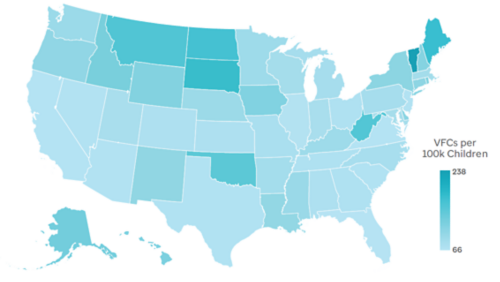

Policymakers and state-level decision-makers should aim to improve VFC provider participation nationwide by increasing the recruitment and enrollment of diverse provider types, such as pharmacists and oral health providers, who could increase access to HPV vaccination for people living in rural areas and for those with lower incomes. Policymakers should also establish a mechanism for payors, health systems, and other trusted providers, such as oncologists, to recruit providers and incentivize their participation in the program. Figure 1 shows the current breakdown of VFC provider types. Figure 2 shows the number of VFC providers per 100,000 children in each state.

Figure 1: VFC Provider Types, 2022

Source: Data provided by CDC, 2022

Figure 2: Number of VFC Providers per 100,000 Children by State, 2022

Source: Data provided by CDC, 2022

Recommendation 4: Expand the resources available to improve HPV vaccination data collection and reporting through state immunization information systems (IISs)

State IISs, or immunization registries, enable health care providers, public health officials, and health care organizations to report, collect, and access information about vaccines administered to individuals at the state or local level. Data collection and reporting have a significant impact on the measurement and evaluation of targeted interventions and the investment of resources to increase HPV vaccination coverage. However, HPV data collection has been inconsistent, resulting in incomplete reporting. Additionally, the systems and platforms through which vaccination data are reported and accessed vary greatly. Interview and focus group participants agreed that standardized, comparable (cross-jurisdiction) data would improve HPV vaccination series completion. In addition, participants noted that data visibility and sharing would give key partners greater insight into HPV vaccination coverage in their communities and regions, helping them to understand how and where to improve coverage.

Medicaid expansion in the 12 non-expansion states is predicted to be associated with more than $10.5 million in savings during the first two years after an HPV cancer diagnosis as a result of increased HPV vaccination initiation and the subsequent reduced incidence of HPV cancers.

A critical first step in improving collaboration among HPV vaccination partners to increase vaccination coverage is establishing reliable and standardized data collection procedures. To do this, state and federal officials should increase funding to improve and expand IIS capacity. Additional funding could be used to improve infrastructure, e.g., by introducing bi-directional cloud-based systems to enable real-time data analysis and visualization reporting (i.e., dashboards). Furthermore, all clinical staff, not only health care providers, should be trained in and educated about accessing the state IISs and entering data promptly and accurately. Finally, establishing a centralized national immunization registry could help standardize immunization data collection to improve reporting methods, vaccination rates, and data quality and coverage.

Recommendation 5: Engage in efforts to preserve and expand eligibility for Medicaid.

Enrollment in comprehensive, affordable, and accessible health insurance coverage is a critical factor in children initiating and being up to date on recommended vaccines in the U.S. Public health insurance programs, such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), have contributed significantly to increased childhood vaccination rates, including vaccination against HPV. Medicaid income eligibility for children varies by age in all 50 states and D.C., with some states having much lower eligibility limits than others.

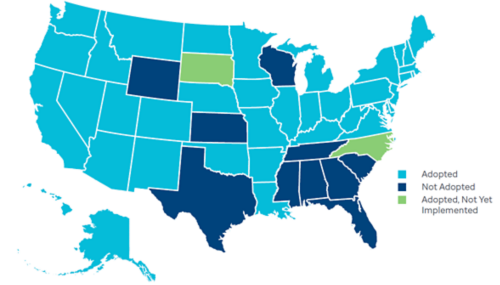

Figure 3: Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision

Experts note that the Medicaid coverage expansion provided for under the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) as a public policy change has been instrumental in increasing HPV vaccination coverage in recent years.13 The ACA provided states with the option to provide low-income adults and parents earning up to 138% of the FPL with access to comprehensive and affordable health insurance coverage through Medicaid. This policy change has resulted in more than 40 states adopting Medicaid expansion, thereby providing more than 18 million lower-income individuals and parents with access to health insurance coverage,14 as seen in Figure 3. As newly eligible parents gained access to Medicaid under the ACA, they also enrolled or re-enrolled their previously eligible children for program coverage – often described as the “welcome mat effect.” As a result, the coverage expansion also helped improve and preserve the access of countless children and adolescents to comprehensive benefits and services through traditional Medicaid programs.

Medicaid provides enrolled children and adolescents with comprehensive preventive and primary care services that span the care continuum, including Early Periodic Screening Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefits that cover well-child exams; hearing, vision, and dental screenings; and other services that help prevent, screen for, diagnose, or treat illnesses or disabilities.15,16 Included in these benefits are all Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)-recommended immunizations, including the HPV vaccine. The ACA’s Medicaid expansion and the related “welcome mat” effect have directly contributed to increased HPV vaccination coverage and series completion in children and adolescents.17

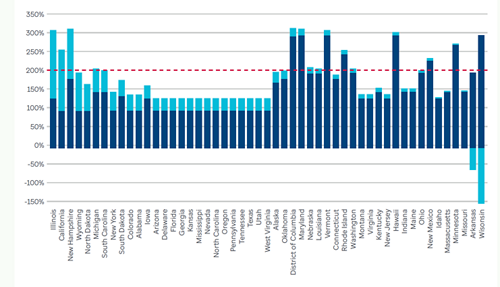

The analysis by FTI Consulting found that eligibility levels for Medicaid among children aged 6 to 18 years had a positive and statistically significant relationship with HPV vaccination coverage. Moreover, the cost savings analysis estimates that increasing Medicaid eligibility to 200% of the FPL in the 32 states with lower eligibility levels could generate approximately $9 million in savings by avoiding medical expenses that are typically incurred during the first two years after an HPV cancer diagnosis as a result of the increased HPV vaccination series completion and the subsequent reduced incidence of HPV cancers (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Change in Medicaid Eligibility for Children 6–18 Years of Age, 2010 to January 2022

These findings demonstrate that increasing access to health insurance coverage through expanded income eligibility for Medicaid has a positive impact on HPV vaccination coverage. Partners, advocates, and policymakers should encourage the 32 states with eligibility levels below 200% of the FPL to consider taking advantage of the opportunities associated with increasing coverage. Partners may also want to consider that advocating for Medicaid expansion in the ten remaining non-expansion states could increase access to primary care and preventive services, including vaccination, for adults and their children.

Conclusion

The introduction and recommendation of the HPV vaccine in the U.S. in 2006 changed the lives of millions of individuals and families in this country; however, there is still a need for significant efforts nationwide to improve access to HPV vaccination, raise awareness of its importance, and increase the number of HPV vaccinations administered to children and adolescents. To increase HPV vaccination initiation and series completion significantly, policymakers, interest groups, and health systems should consider a combination of existing and new policies, specifically those discussed in this report.

The long-lasting implications of raising HPV vaccination initiation and series completion rates would manifest in several ways; not only can HPV vaccination reduce the incidence of HPV cancer from more than 37,000 diagnoses every year,2 but the nation’s health care system could realize millions of dollars in savings. FTI Consulting’s findings show that the increased HPV vaccination initiation and reduction in HPV cancer incidence as a result of addressing the four actionable policy factors tested in the regression analysis, i.e., meningococcal conjugate vaccination coverage, Medicaid eligibility expansion, access to VFC providers, and access to pediatricians, could reduce national direct health care expenditures by nearly $19 million. Likewise, the cost savings analysis estimates that the increased HPV vaccination series completion and reduction in cancer incidence as a result of addressing these four factors could reduce the two-year national direct health care expenditures by more than $24 million.

The long-lasting implications of raising HPV vaccination initiation and series completion rates would manifest in several ways; not only can HPV vaccination reduce the incidence of HPV cancer from more than 37,000 diagnoses every year,2 but the nation’s health care system could realize millions of dollars in savings. FTI Consulting’s findings show that the increased HPV vaccination initiation and reduction in HPV cancer incidence as a result of addressing the four actionable policy factors tested in the regression analysis, i.e., meningococcal conjugate vaccination coverage, Medicaid eligibility expansion, access to VFC providers, and access to pediatricians, could reduce national direct This report has aimed to provide a roadmap for the hopeful future of HPV cancer prevention through increased HPV vaccination coverage, as well as to inspire partners, advocates, and interest groups. At the core of our recommendations are several universal themes that must be prioritized in the next stage of HPV advocacy. These are requirements for a collaborative effort between local, state, and national HPV vaccination and cancer prevention leaders; an understanding of the differing needs of local communities, regions, and geographies and of the potential impact of targeted approaches on HPV vaccination coverage efforts and strategies; consistency in cancer prevention messaging and education; and the setting of standards for how care related to HPV can be delivered, measured, and improved. These resources and the other tools offered in this report can increase HPV vaccination rates and reduce the number of individuals and families facing a diagnosis of preventable cancer.

The evidence is indisputable: HPV vaccination is cancer prevention. Unfortunately, the U.S. continues to underutilize the vaccine’s power as a lifesaving cancer prevention tool, as demonstrated by the nation’s suboptimal HPV vaccination coverage. For society to reap the full benefits of this vaccine, policy change must be pursued at multiple levels to address systemic barriers to HPV vaccination coverage and provide a long-lasting, sustainable, meaningful, and measurable impact. Through policy change, partners and advocates can prioritize, promote, and change social norms to improve population health for generations. The pursuit of evidence-based policy change will enable us to realize the full potential and promise of the HPV vaccine – the complete eradication of HPV cancers.

References

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, February 10). HPV infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 20, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, October 3). HPV-associated cancer statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 20, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm (now https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/cases.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, November 1). Cancers caused by HPV are preventable. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 20, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/protecting-patients.html

4Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, October 3). How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 20, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/cases.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

5 Lairson, D. R., Fu, S., Chan, W., Xu, L., Shelal, Z., & Ramondetta, L. (2017). Mean direct medical care costs associated with cervical cancer for commercially insured patients in Texas.. Gynecologic Oncology, 145(1), 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.02.011

6 Fu, S., Lairson, D. R., Chan, W., Wu, C.-F., & Ramondetta, L. (2018). Mean medical costs associated with vaginal and vulvar cancers for commercially insured patients in the United States and Texas. Gynecologic Oncology, 148(2), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.019

7 Lairson, D. R., Wu, C.-F., Chan, W., Fu, S., Hoffman, K. E., & Pettaway, C. A. (2019). Mean treatment cost of incident cases of penile cancer for privately insured patients in the United States. Urologic Oncology, 37(4), 294.e17–294.e25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.01.004

8 Wu, C.-F., Xu, L., Fu, S., Peng, H.-L., Messick, C. A., & Lairson, D. R. (2018). Health care costs of anal cancer in a commercially insured population in the United States. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 24(11), 1156–1164. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.11.1156

9 Lairson, D. R., Wu, C.-F., Chan, W., Dahlstrom, K. R., Tam, S., & Sturgis, E. M. (2017). Medical care cost of oropharyngeal cancer among Texas patients. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 26(9), 1443–1449. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0220

10 Fu, S., Fokom Domgue, J., Chan, W., Zhao, B., Ramondetta, L. M., & Lairson, D. R. (2019). Cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancer costs incurred by the Medicaid Program in publicly insured patients in Texas. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 23(2), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000472

11 Zhao, B., Fu, S., Wu, C.-F., Dahlstrom, K. R., Fokom Domgue, J., Tam, S., Xu, L., Sturgis, E. M., & Lairson, D. R. (2019). Direct medical cost of oropharyngeal cancer among patients insured by Medicaid in Texas. Oral Oncology, 96, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.06.033

12 Anuforo, B., McGee-Avila, J. K., Toler, L., Xu, B., Kohler, R. E., Manne, S., & Tsui, J. (2022). Disparities in HPV vaccine knowledge and adolescent HPV vaccine uptake by parental nativity among diverse multiethnic parents in New Jersey. BMC Public Health, 22, 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12573-7

13Roberts, M. C., Murphy, T., Moss, J. L., Wheldon, C. W., & Psek, W. (2018). A qualitative comparative analysis of combined state health policies related to human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 108(4), 493–499. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304263

14KFF. (2022, September). Medicaid expansion enrollment. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-expansion-enrollment/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

15Medicaid.gov. (2023, March). March 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights. Medicaid.gov. Retrieved July 20, 2023, from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html

16Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2018, January 19). Medicaid Works for Children. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-works-for-children#medicaid-improves-access-to-care-cbpp-anchor

17 Hawkins, S.S., Horvath, K., Cohen, J. et al. (2021). Associations between insurance-related affordable care act policy changes with HPV vaccine completion. BMC Public Health, 21, 304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10328-4

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital or its staff or those of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals. Primary contributors to this study were Heather M. Brandt, PhD, Citseko Staples Miller, Susan Henley Manning, PhD, Sabiha Quddus, Kristy Pultorak, Sherry Wang, Sanjana Muthukrishnan, Danielle Poindexter, Natalia Vasquez, Ashley Warren, Ronelle Green, Andrea Stubbs, and Rob Clark. Research completed in May 2023.