St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Assessing global pediatric cancer: Finding out what we don’t know and reaching more children

Nikhill Bhakta, MD, left, consults with Carlos Rodriguez-Galindo, MD. Bhakta recently published a review identifying what is needed to organize a global initiative to improve pediatric cancer survival rates.

Over the past two years, the global community has made major progress in recognizing the health inequities in global pediatric cancer. Although over 80 percent of children in high-income countries like the United States with cancer are potentially cured, we know this figure in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is much lower.

Despite this gap, we still cannot put a clear answer to it nor answer the basic questions necessary to guide health policy and cancer control planning. More concretely stated, we still do not know how many children develop, are diagnosed with, are treated for and ultimately survive cancer worldwide each year. Without this basic information, stakeholders interested in improving childhood cancer survival in the most resource-limited settings are left to work blind, uncertain of where to start or whether tangible progress is being made.

In a recently published paper from The Lancet Oncology titled “Childhood cancer burden: a review of global estimates,” we worked with a team comprised of the world’s experts in cancer burden epidemiology to highlight what we know now, frankly acknowledge the gaps in our current data and clearly articulate how the scientific community can help improve our tracking of childhood cancer outcomes.

Global pediatric cancer is about children, not adults

Although the science is complex, two key limitations stood out. First, although pediatric cancers are fundamentally different from those seen in adults, most global experts apply adult-biased methods when working with childhood cancer data. To improve the relevance and quality of information on childhood cancer burden, data collection and analytic approaches that are specific for children and adolescents are required.

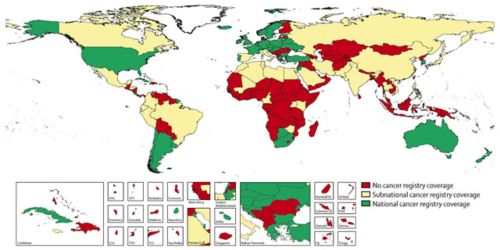

Additionally, the quantity and quality of data from LMIC are lacking. Cancer registries, the key tool to monitoring and tracking the health of a population and success of a cancer treatment program, do not exist in many countries. Without investments in these systems, making informed decisions for how best to spend precious limited resources is near impossible.

Recommendations to measure global pediatric cancer burden

After reviewing the available data and dissecting the pitfalls in the current methods used globally, our team developed several key recommendations for public health experts, governments and funding agencies to consider:

- Due to the lack of data from which to quantify global childhood cancer outcomes, there is a critical need to support existing cancer registries to improve the quality of data collected while also helping support new cancer registries, particularly in LMIC countries.

- Formulate frameworks and standards to encourage timely data sharing between hospital-based and population-based registries on a national level, and global burden estimation groups on an international level. With rapid changes in global data privacy laws due to recent controversies involving companies like Facebook and others, there is less certainty now more than ever regarding where the lines between maintaining the public health interest end and ensuring personal privacy protection start.

- In the face of limited data, the scientific community will need to develop new models, not biased by adult cancer methodologies, to estimate the global childhood cancer burden. Cancer is not a single disease and there are real differences in how adult cancers and children’s cancer are counted. Delinking adult and pediatric cancer estimates will allow for additional flexibility and innovation.

- Create and disseminate cancer registration training curricula and opportunities that are specific to childhood cancer.

Additional recommendations regarding education, standards and cooperation were also discussed in the final report.

What can we do better?

Improving global estimates of childhood cancer burden, and by extension, improving global childhood cancer control programs, is not something that will occur overnight. Taking a step back and doing a self-assessment, as a community, and honestly asking “what can we do better” as we did was an important first step. Although some improvements can be implemented quickly, several will require structural changes and will take time and additional financial resources. However, with growing momentum behind childhood cancer after the 2017 World Health Assembly cancer resolution and the recently launched World Health Organization Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer, now is the time to get started.