St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Managing pain without enabling opioid addiction

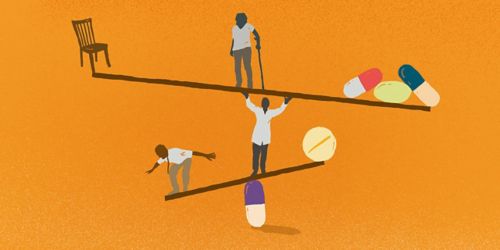

To help prevent the possibility of misuse of opioids, clinicians can find the balance in their patients to better understand anxiety, stress and pain management.

The opioid crisis has been making headlines for the past few years, but this politically charged term often oversimplifies a complex issue in order to assign responsibility for the growing problem of addiction.

The fact is, opioid prescribing has been on the decline since 2010, decreasing more than 8% annually since 2014. For high-dosage opioids (≥ 90 morphine milligram equivalents /day), the decline has been even sharper — more than 50% since 2006. Despite efforts by providers to prescribe opioids more responsibly, drug overdose-related deaths continue to set record highs each year. (1)

In 2017, drug overdoses killed more than 70,000 Americans, higher than car crash, HIV, or gun deaths at their peaks. For the first time since World War II, life expectancy in the U.S. has decreased for three years in a row. (2)

Overdose-related deaths are driven largely by illegal drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and synthetic opioids, namely illegally manufactured fentanyl. (Fentanyl-related deaths spiked almost 50% in 2017 alone.) However, this doesn’t lessen the burden of responsibility of the health care providers and drug manufacturers, as often the consumption of illicit drugs is started by a “point-of-entry” of being exposed to legally prescribed opioids for pain.

So how can we as health care providers practice compassionate medical care safely and responsibly, especially when facing patients who may experience substantial pain and may need the prescription of strong opioids? According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a low percentage of those needing treatment for substance abuse have access to it. The practitioner’s dilemma more than ever is to treat pain compassionately while exploring comprehensive treatment options, in which opioids play a limited role in a multimodal approach, in order to prevent opioid addiction and abuse.

At St. Jude, a recent case involving a young adult with cancer presented our team with a difficult situation — a patient who needed palliative care, but who also manifested signs of addiction and opioid abuse. The ultimately successful solution shows a way to manage pain in patients of all kinds, regardless of whether they have previously exhibited risk factors for addiction.

In the case of the young adult with cancer, “Michael” was experiencing not just physical pain from his disease, but also terrible anxiety related to his treatment and his end-of-life care. We learned that he was activating his morphine bolus doses (from his prescribed patient-controlled analgesia device) not just when he was in pain, but also when he was depressed, anxious, or emotionally upset in any way.

This emotional distress was understandable given Michael’s situation. And one may wonder why addiction or opioid abuse would be a high level of concern for a patient in palliative care. But the fact is that opioids, while appropriate to treat cancer-related pain, are the absolute wrong treatment for anxiety and depression. They won’t relieve the symptoms, nor will they address the underlying problem. If the object of palliative care is to relieve pain — physical or emotional — during end of life care, then appropriate individualized treatment must be used.

In Michael’s case, what worked was a multimodal and multidisciplinary treatment approach that provided him with better analgesia and coping skills for anxiety. Simply put, we limited opioids to treatment of his physical pain and used a combination of psychological therapies to manage his anxiety and depression.

Implementing this multimodal approach is anything but simple. It requires understanding patients well enough to know where the balance lies. How accurate are their self-assessments of pain? Does their history suggest a susceptibility to either opioid misuse or psychosomatic conditions? How can we be sure we are not under managing pain in our efforts to be responsible prescribers?

Those are just a few of the questions we providers face. Tackling them from the outset is critical to our efforts to provide effective analgesia that doesn’t encourage or exacerbate opioid abuse.

(1) https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf