St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Why cancer survivors should take part in long-term follow-up studies

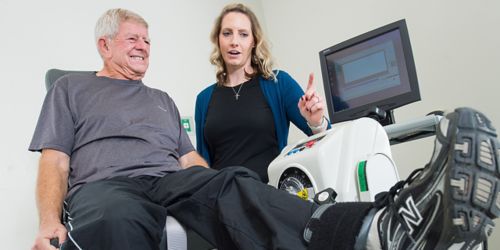

Dwight Tosh, left, performs leg exercises during a fitness test at St. Jude. Robyn Partin, senior exercise specialist, supervises.

More than 55 years ago, Dwight Tosh was patient No. 17 at a fledgling hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. Today, he helps researchers learn more about the long-term effects of cancer and its treatment.

I was the first in St. Jude LIFE.

It’s the dream of every patient at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital — to be cured of your disease, and, years later, to be able to look back on a long life, well-lived.

Prior to coming to St. Jude in 1962, I was in the hands of several doctors who diagnosed me with Hodgkin lymphoma. Finally, they told my parents, “We’ve done all we know to do. You need to prepare for the worst.” They gave me maybe a week to live—two weeks at the most.

Then St. Jude opened its doors. They loaded me into an ambulance and transported me to Memphis, where I was literally carried into the hospital. There, my family was given something we didn’t have before—hope. Suddenly, we had a chance to defeat something that had taken hold of us and caused the darkest hour of our lives.

Eventually, there came that moment when the doctors said, “The cancer is gone. We’ve won this battle.” I left St. Jude to resume my life. I grew up and married my high school sweetheart. We had two wonderful kids and four outstanding grandchildren.

In 2007, the hospital opened a long-term follow-up study for cancer survivors like me. Over the course of my lifetime I had experienced a few health problems. A second cancer. Heart issues. Joint problems. Diabetes. I'd often wondered if those were complications of my long-ago cancer treatments.

The idea of joining the St. Jude LIFE study was intriguing. Would the doctors be able to connect those issues to particular treatments I received back in the ‘60s? Could they take that information and use it to help other patients? Could doctors possibly prevent such problems from occurring at all?

By taking part in St. Jude LIFE, I might possibly help some other children along the way.

An added bonus was the study might help identify additional health issues I should address. I visit my hometown doctor on a regular basis, but you never know what might be going on.

It was a win-win situation for me.

So, 10 years ago, I was the first patient to come back to campus and take part in the St. Jude LIFE long-term follow-up study. I went through several days of tests—of my heart, lungs, blood, fitness, balance and many other things. They drew blood, took X-rays and made me run on a treadmill. It was a busy week.

Since that time, more than 5,000 other St. Jude cancer survivors have enrolled in St. Jude LIFE. Like me, those individuals are finding out how their childhood cancer treatments affect their current health. They’re also learning lifestyle tips that can improve their outlook for the future.

Almost every one of those survivors has been found to have at least one chronic health condition related to their disease or its treatment. That’s information clinicians can use as they design cancer treatments for children who come after us. The scientists are also figuring out how genetics contribute to cancer risk. The researchers have already published about 85 papers on their findings. And they’re sharing that information with doctors around the world.

I'm grateful for the opportunities I’ve been given. Out of that gratitude, I’m happy to come back to participate in this research. I never want to get so busy that I forget why I'm able to live the life that I'm able to live.