St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Searching for the next pandemic flu virus? There’s another factor to keep in mind.

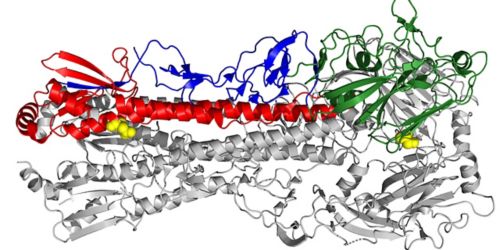

This electron microscopy image of an influenza virus shows the stability altering residues, highlighted in yellow, that effect the pandemic capacity of swine flu.

Before COVID-19, influenza was the virus most associated with pandemics. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic swine flu virus was the first pandemic of the 21st Century. The virus killed upward of 575,400 people worldwide. Federal health officials estimate 60.8 million U.S. residents were infected and close to 12,500 died.

In the middle of the current pandemic, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientists are working hard to enhance the global flu surveillance system and improve their ability to recognize animal viruses with the most potential to cause a pandemic. Current flu surveillance includes monitoring a variety of environmental, epidemiological and viral factors.

Pandemic potential expanded

Research led by Charles Russell, PhD, of St. Jude Infectious Diseases, identified another trait to consider when evaluating the pandemic potential of animal viruses. That is the stability of the hemagglutinin (HA) protein. The findings appeared this week in the journal eLIFE. Meng Hu, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Russell’s lab, is the first author.

HA is the surface protein the flu virus uses to bind to and invade host cells. HA binding preferences vary by species. To bind human cells, the HA of avian and swine flu viruses must adapt. HA also triggers the immune response that combats the infection. A novel HA puts the immune system at a disadvantage, forcing it to play catch up after infections have started. Investigators currently track both aspects of HA—binding and novelty—to spot animal viruses with pandemic potential.

Russell and his colleagues reported that HA stability in mildly acidic conditions like those in the human upper respiratory tract also factor into the pandemic potential of swine flu viruses.

Setting conditions for airborne transmission

Scientists knew HA binding is just one step. Infection requires that binding be followed by fusion of virus and host cell membranes, then release of the viral genome into host cells and production of more flu virus. Human flu viruses have a relatively stable HA. Protein activation and viral genome release occurs at a mildly acidic pH of 5.5 or less. The HA is typically less stable in animal viruses. Their preferred pH, or the pH of activation, is typically higher at pH 5.5 or above.

Researchers reported that HA stability promoted airborne transmission of swine flu viruses in ferrets, which model human flu infections. Airborne transmission is an established indicator of flu viruses with pandemic potential. “This study and others show that the stability of the HA protein should be considered along with receptor binding when evaluating the pandemic potential of a flu virus,” Russell said. The findings build on Russell’s 2016 paper that showed that a human pandemic flu virus lost its pandemic capacity when the HA was destabilized. The paper was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The viruses varied widely in HA protein stability and included HA genes that are closely related to the 2009 pandemic virus. When researchers compared airborne transmission in ferrets, the virus that transmitted most effectively had an HA that was stable and adapted for binding the human receptor.

“This work drives home that we need to think about these HA properties as partners that travel together,” Russell said. “Both are necessary for viruses to become transmissible in humans. Surveillance systems should be expanded to reflect this.”

The swine flu viruses in this study were collected as part of the hospital’s role as a Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance for the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The institution is also a collaborating center with the World Health Organization Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System.