St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Safeguarding futures by mapping the developing brain

Learn how discoveries in brain development from cell identity to genetic predisposition are providing a fresh outlook on childhood health and disease

The connections made between cells during embryonic development and as a child grows are hardwired by genetics and defined by function. But the cells within the developing brain have a unique path to follow. A newborn child’s brain is a quarter the size of an adult brain; by age 5, it is almost full size. Each neuron produced and each connection made before and during this vital period reflects a child’s experiences in the world. Pediatric neurological diseases derail this delicate process, altering not just the formation of neural circuits necessary to become healthy adults, but often the experiences and possibilities that define a life.

While the developing brain can seem a complete product of its environment, it is also defined by carefully managed biological processes. Modern technologies and newly developed models have provided scientists with unmatched access to the brain’s true origin story: one of cell genesis, spatial arrangement and genetic predisposition. Understanding these factors and how pediatric diseases interfere with them is essential not only for diagnosing and treating them, but for understanding the delicate balance between neural function and dysfunction. At St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, scientists are piecing together the matter behind the mind to address the disorders that arise when this complex process goes awry.

The genes that define cell fate

Neural development resembles a career ladder, with each rung marking greater specialization. This begins within the neural tube, an embryonic structure that develops into the central nervous system. Pluripotent (immature) stem cells, which can become any cell type, become neural stem cells that are inclined toward a neural career path but only commit when they become neural progenitor cells. These cells undergo neurogenesis to become neurons, which form synaptic networks in the brain, or gliogenesis to become glial cells, which provide structural and functional support.

“Neural progenitors are the basis of many pediatric brain tumors and neurodevelopmental disorders,” says Jamy Peng, PhD, Department of Developmental Neurobiology, left, “And the cellular machineries I study are closely tied to disease.” Also pictured, Xiaoyang Yang MD, PhD, St. Jude Children’s GMP, center, and Beisi Xu, PhD, Center for Applied Bioinformatics.

All neural cells go through some version of these processes, and Jamy Peng, PhD, Department of Developmental Neurobiology, seeks to understand the genetic programs that define them. “My focus is on function; why these genetic programs are so crucial,” said Peng. “Neural progenitors are the basis of many pediatric brain tumors and neurodevelopmental disorders, and the cellular machineries I study are closely tied to disease.”

Peng studies the job counselors that steer neural progenitors through their career options. Depending on the development timeline, however, options may be limited. Neurons are needed most during embryonic development. Glial cells are usually formed after neurons, acting as a ground crew to maintain the neuronal network. This “choice” is largely defined by gene access. DNA is tightly wound around proteins called histones to form chromatin, the storage form of DNA. When tightly wound through a process called histone methylation, access to genes is restricted. This process is more specifically called “H3K27” methylation, meaning a lysine (denoted by the symbol K) at position 27 on histone H3 has a methyl group attached to it. In contrast, histone demethylation loosens things up, allowing gene access.

The protein UTX acts as an early career counselor, demethylating histone lysine 27 to relax chromatin and allow gene access. In a 2020 Epigenetics & Chromatin study, Peng showed how UTX enables access to key genes associated with neurogenesis, driving the neural progenitor cell to become a neuron, while also blocking systems that drive gliogenesis.

Opposing UTX’s role as neuron advocate is PRC2. PRC2 helps methylate histones to tighten up chromatin and switch off neurogenesis-supporting genes. This “gene silencing” switches emphasis from neurogenesis to gliogenesis but must be tightly regulated because over-methylation and under-methylation have both been implicated in disease.

To better understand how PRC2 methylation is regulated, Peng explored its binding partners. In a 2020 Nature Communications paper, her team identified the RNA-binding protein YBX1 as a crucial component to this control. They found that YBX1 acts as a supervisor, fine-tuning the timing and location of neurodevelopmental gene expression.

“Negative regulation of PRC2 by YBX1 instructs neurogenesis. Interestingly, YBX1 overexpression has been implicated in glioblastoma,” said Peng. “We are now digging into PRC2-YBX1 imbalance in glial tumors.”

Brain atlas expands our understanding of where signals begin

Once a neuron is formed, its career journey is far from complete. As the neural tube grows, a carefully balanced chemical gradient defines neuron specialties. Sensory neurons detect environmental stimuli and send signals. Motor neurons turn this signal into action. And a diverse class of signal liaisons called interneurons relay messages between the two.

Jay Bikoff, PhD, Department of Developmental Neurobiology, studies a group of interneurons found in the spinal cord called V1 interneurons that play an important role in movement. V1 interneurons are inhibitory, meaning they help shape motor neuron signaling by restricting it to fine-tune movement.

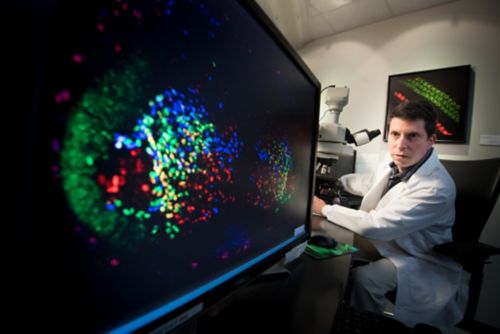

“Our work, among others, is helping to map out the functional logic of these complicated pathways connecting the brain and spinal cord,” says Jay Bikoff, PhD, Department of Developmental Neurobiology.

“My lab uses mouse genetics to study the neurons that form circuits that directly control movement,” Bikoff explained. “We use different strategies to identify how V1 interneurons fit into this larger cellular ecosystem, including how they connect and transfer information to other neurons, and ultimately what they might be doing in terms of controlling motor output.”

As the brain develops, descending motor pathways from the brain send long, threadlike axons all the way to the spinal cord, thereby helping to shape coordinated movement. And while their impact on disease is still being uncovered, controlling V1 input to motor neurons has been suggested to help slow neurodegenerative disease progression.

“Stabilizing V1 interneuron input to motor neurons may ultimately be one way to help improve stepping function in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” Bikoff explained. “In other cases, reducing inhibition may improve function, for example, in spinal muscular atrophy. It really depends on the context.”

To better understand the fundamental system that governs this signaling, Bikoff’s team interrogated the connections that run through V1 interneurons. This resulted in an interactive atlas of the mouse brain, published in 2025 in Neuron, that reveals where the signals received by V1 interneurons come from in the brain.

The researchers uncovered 26 distinct brain regions that relay signals through V1 interneurons, helping them define several dozen different pathways that issue commands to these spinal interneurons, demonstrating how high the career ladder really gets for neurons. “These descending pathways were known, but there’s been a recent expansion in our knowledge of what different parts of the brain are doing,” Bikoff explained. “Our work, among others, are helping to map out the functional logic of these complicated pathways connecting the brain and spinal cord.”

“Rather than abnormal electrical activity in the brain, the cells themselves are inherently altered by variants that disrupt development, migration and signaling, all of which contribute to developmental differences,” explains Heather Mefford, MD, PhD, Department of Cell and Molecular Biology.

Using genetics to get to the root of developmental disorders

To complement the fundamental insights gained from Peng and Bikoff, neurogeneticists, such as Heather Mefford, MD, PhD, Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, are returning to the genetic blueprint that orchestrates brain development long before a neural progenitor cell takes shape. Mefford studies developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEEs), a series of neurological conditions characterized by seizures in combination with developmental delays that usually start in early childhood.

Historically, delays were attributed directly to the seizures, but growing knowledge is demonstrating this is not the case. “In DEEs with an identified genetic cause, the defect is present in every cell from conception,” Mefford explained. “Rather than abnormal electrical activity in the brain, the cells themselves are inherently altered by these variants that disrupt development, migration and signaling, all of which contribute to developmental differences.”

Several hundred identified genes are linked to DEEs, but this only represents about 50% of DEE cases. Mefford has made it her mission to keep chipping away at the remaining cases, because only when clinicians and parents know the cause can they truly address the issue.

Chromatin remodelers, such as those Peng studies, are a prominent source of DEEs. Mutated chromatin remodelers can alter processes such as methylation, derailing cell development and knocking neural progenitor cells off their trajectory. Still, within this disruption is a silver lining.

DNA methylation works similarly to histone demethylation to silence genes. DNA methylation also leaves behind a distinctive pattern — a molecular fingerprint — on DNA. In a 2024 Nature Communications paper, Mefford and her team explored whether the unique DNA methylation pattern caused by a mutated gene, called an “episignature,” could trace DEE to its genetic culprit.

As a proof of concept, the researchers successfully utilized this strategy on a commonly mutated DEE gene, CHD2. “CHD2 is expressed in every cell, but the outcomes [early onset, severe epilepsy] are restricted to the brain,” Mefford said. “This is due to the set of genes specific to the brain that CHD2 turns on or off, which is now disrupted.”

They confirmed that CHD2 mutations that cause DEE led to distinct methylation pattern changes that impact gene access, and thus, cell development. This showed that the approach can act as a fingerprint to help diagnose future DEE patients. In fact, the researchers successfully used this approach to identify a further 12 previously undiagnosed cases within their sample population.

Making life-long connections by understanding brain development

The nature of how the brain develops can make pediatric neurological disease a lonely experience. One key outcome for studying brain development is the ability to put a name to a condition, based on its genetic origin. This can give a family access to an advocacy network, aiding in emotional support and unifying a small but passionate group under a common goal. Each new gene identified and each new connection understood may be the breakthrough for which a family is hoping.

As researchers, such as Peng, Bikoff and Mefford, piece together the story of the developing brain, their work represents a commitment to understanding the foundations of life and safeguarding children’s futures. By exploring the ancestry of cells, the connections they make, and the genetics that define their function, each discovery contributes to transforming the outlook of children affected by neurological disease.