St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Innovation propels an immunotherapy ‘growth spurt’

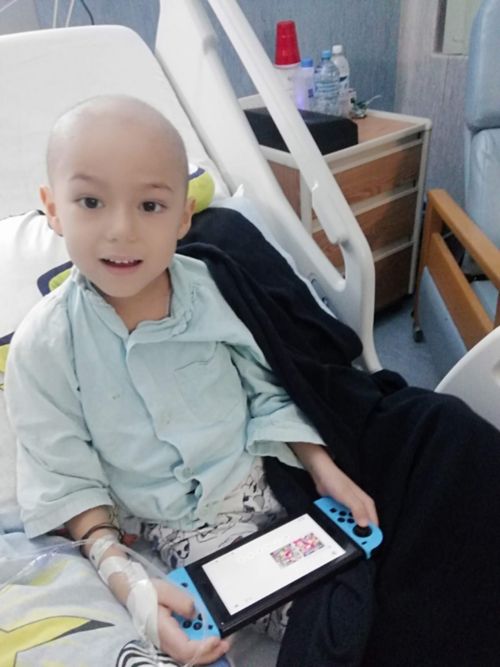

Alfonso will soon outgrow his favorite shoes after his latest growth spurt, which occurred two years after he completed CAR T–cell therapy at St. Jude.

Alfonso grew five centimeters in the six months between February and August 2025. While such a growth spurt is a standard developmental milestone for most 12-year-old boys, Alfonso is not most 12-year-old boys.

Now as tall as his mother, Alfonso and Monica navigate the halls of St. Jude together.

Now eye-level with his mother, Monica, it is easy to see how much Alfonso has grown from the small 8-year-old boy who first came to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in 2022. Not yet at ease with his new stature, he glances at his vibrant high-top sneakers or into the animated screen of his Nintendo as he and his mother sit side-by-side in the Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy waiting room at St. Jude.

For Monica, her son’s stature serves as a reminder of a time when his growth was not so certain. Shortly after the 2019 New Year, the then 5-year-old Alfonso began needing more rest. “He would sleep more, and when I looked in his eyes, he just looked different,” she says. When she took him to the pediatrician, bloodwork showed leukemia.

In the early days of treatment in Mexico, Alfonso played games to pass the time.

Alfonso was admitted to the children’s hospital in his hometown of Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico, where he began chemotherapy almost immediately. Further tests showed the type of cancer to be B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). Arising from mutations in genes that regulate and control the development of B cells (the lymphocytes, or white blood cells, that make antibodies to fight infection), B-ALL is the most common type of pediatric leukemia and the most common subtype of ALL.

Eight months after treatment began, Alfonso’s leukemia returned, and he needed a bone-marrow transplant to target the cancer at its source. Alfonso was transferred to the Pediatric National Institute in Mexico City, where he was scheduled to receive the transplant. However, in March 2020, the COVID pandemic stopped all but emergency procedures at hospitals worldwide. He continued to receive chemotherapy while he waited. It was August 2021 before Alfonso received the necessary transplant, and while it initially appeared successful, he relapsed again a little over a year later.

Alfonso steps over hurdles in physical therapy at St. Jude.

Alfonso’s parents were appreciative of the palliative care the hospital offered, but they were determined to find a cure for their then 8-year-old son. They were soon connected to contacts in Memphis, Tennessee, USA, and a referral brought them to St. Jude, where clinicians and investigators were conducting a clinical trial to evaluate a different type of therapy, called immunotherapy, to treat relapsed ALL.

Investigating the therapeutic potential of a patient’s immune system

Immunotherapy — using a persons’ own immune system as the basis for treatment — is a concept that first surfaced in the late nineteenth century. While several approaches can harness the power of the immune system to fight disease, one approach that was developed in the last 30 years, called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T–cell therapy, has proven advantageous for treating blood cancers.

Alfonso stands outside the AutoZone Park in Memphis, TN, USA after watching a baseball game with his sister, Elisa, and his parents, Monica and Alfonso.

CAR T–cell therapy genetically modifies a patient’s T cells (the lymphocytes, or white blood cells, that provide immune protection against infections) so they can target and attach to proteins on the surface of a cancer cell, thereby helping the T cells destroy the cancer cell. To do this, T cells are collected from the patient’s blood and modified in the laboratory to express the receptor that has been designed to detect particular proteins on the surface of a cancer cell. Before infusion of these CAR T cells, the patient receives a four-to-five-day course of chemotherapy so the modified cells can better multiply and seek the cancer cells they have been optimized to detect and destroy.

When pediatric oncologist Aimee Talleur, MD, Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy, met Alfonso in 2022, she knew that after years of chemotherapy, a transplant and two relapses, CAR T–cell therapy was the next best step. In fact, Talleur was co-principal investigator on SJCAR19, the first clinical trial at St. Jude to study CAR T–cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory B-ALL. Patients who, like Alfonso, needed another option.

Monica describes the opportunity to come to St. Jude and enroll in SJCAR19 as “if our family was being handed a golden ticket.” That golden ticket would soon lead to staggering growth for Alfonso and the future of immunotherapy at St. Jude.

Alfonso shows his pediatric oncologist, Aimee Talleur, MD, a scene from his latest favorite Nintendo game, The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom.

A golden ticket for growth in immunotherapy with SJCAR19

Alfonso and his parents were not the only ones to view SJCAR19 as a golden ticket for growth. Clinicians and investigators had been working for well over a decade to bring the reality of CAR T–cell therapy to St. Jude.

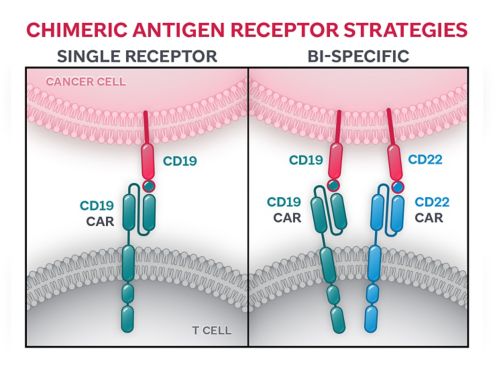

CD19 antigens are proteins that are frequently expressed on the surface of B-ALL cancer cells. It was well known that CAR T cells could successfully target and bind to CD19, and while clinical implementation of the approach was showing progress across the field, St. Jude researchers thought they could improve it. In the early 2000s, they focused on improving the design of the CAR by modifying its structure. The new design leveraged different signaling pathways to activate the T cells once the CAR recognizes CD19. This St. Jude CD19-CAR, developed by Dario Campana, PhD, and his team of investigators that included Chihaya Imai, MD, PhD; Ching-Hon Pui, MD, Department of Oncology; and Terrence Geiger, MD, PhD, senior vice president, was published in Leukemia in 2004.

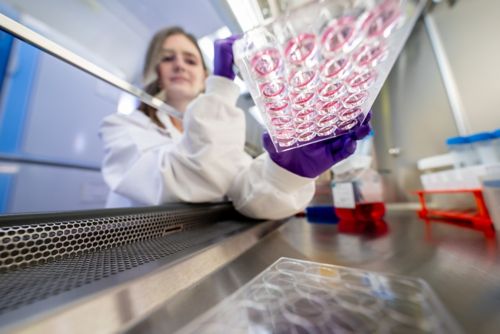

Graduate student Bailey Bridgers prepares tissue cultures as part of Paulina Velasquez’s laboratory work on CAR T cells.

However, it would be years before the new CAR product would make it from the laboratory into the clinic. While all the necessary pieces — the scientific expertise, the clinical prowess and the gene-manufacturing facility — were at St. Jude, investigators had to learn how to place them together in a translational way to create a pipeline from bench to bedside and back.

Developing a pipeline for continued growth in CAR T–cell therapy

When Stephen Gottschalk, MD, chair of the Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy and co-investigator for SJCAR19, joined St. Jude in 2017, he had been studying CAR T–cell therapy for years.

“Cell therapy is like a multicellular organism where different components must come together. Building the cell therapy pipeline at St. Jude was no different. We really needed a team-science approach, and it happened to be the right time to do this,” Gottschalk says.

Strategies for CARs to detect and attach to particular antigen(s) expressed on the surface of a cancer cell range from (i) a single-receptor approach, in which the CAR is designed with only one domain to detect one cancer antigen, to (ii) a bi-specific approach in which two separate domains — engineered to detect two separate cancer antigens — are placed on the surface of the CAR.

By 2018, a CAR-focused immunotherapeutic translational pipeline was operational, and SJCAR19 had been launched to validate the safety and efficacy of the St. Jude-designed CD19-CAR. Alfonso received his CAR T–cell treatment on the same trial four years later, in November 2022.

With the foundation set, the CAR T–cell therapy program at St. Jude was poised for growth.

The next-generation of CAR T–cell trials

“Our research program is built upon intensive correlative testing that focuses on learning as much as possible from every single patient that’s enrolled in a clinical trial. We try to understand what is happening to the CAR T cells and other immune cells in the patient’s body during therapy,” Talleur says. Paulina Velasquez, MD, Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy, leverages all the knowledge she can from patient data collected during clinical trials. Her work aims to better engineer CAR T cells and apply them across various blood malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and T-cell ALL (T-ALL).

“You learn from the patient outcomes, but you also learn from the samples you collect from the patient, and these are very valuable. We make the most of the information we get so we can help other patients,” Velasquez says.

While SJCAR19 helped patients, there was still a need to innovate and improve. In about half of patients, B-ALL returns after successful CD19-CAR T–cell therapy. At the time of relapse, the leukemia cells have often lost expression of CD19, making them invisible to the CD19-CAR T cells that were previously infused. To overcome this problem, Velasquez and Gottschalk worked together to develop a new CAR T–cell product that targets two highly expressed antigens in B- ALL: CD19 and CD22. The safety and efficacy of the new bi-specific CAR is being evaluated in a first-in-human trial called 1922CAR.

Rebecca Epperly, MD, Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy, began her St. Jude career as a hematology/oncology fellow in Velasquez’s laboratory, where she researched how best to engineer and utilize this bi-specific CAR design. Epperly is now the principal investigator of the 1922CAR study, with Talleur serving as her mentor.

“It is like having big sisters in cell therapy,” Epperly says. “It’s exciting to take what I’ve learned from the mentorship I’ve received and apply it to an area I can really contribute to, effectively transitioning the work I did in the lab to the clinic.”

The “big sisters in cell therapy” — Aimee Talleur, MD; Rebecca Epperly, MD; Paulina Velasquez, MD; and Swati Naik, MD — discuss progress across their CAR T–cell research.

Further emphasizing the translational underpinning of the CAR T–cell therapy program at St. Jude, Talleur explains how continued analyses of SJCAR19 data drive additional trials that seek to understand other factors that could impact CAR T–cell efficacy. One such focus area is around the dose of chemotherapy given to a patient before CAR T–cell infusion. While it is known that giving chemotherapy before CAR T cells is needed to help the CAR T cells grow and work, the optimal regimen is not yet known.

Using data from the SJCAR19 clinical study, researchers wanted to better understand how different metabolism rates in children affect how well CAR T cells work after infusion. Results from the analysis, led by Markos Leggas, PhD, Department of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences, and published in Blood Advances in 2025, showed younger children metabolize chemotherapy faster than older children, demonstrating a need to explore age-adjusted chemotherapy dosage as part of the CAR T–cell therapy pipeline. CAR19PK aims to do just that. Co-led by Swati Naik, MD, Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy, and Talleur, the trial assesses the impact of age-adjusted doses of chemotherapy on CD19-CAR T cell performance over time.

“Recent data have shown that the dose of chemotherapy given prior to CAR T–cell infusion influences responses. We can no longer use a one-size-fits-all approach and need to adopt a personalized, tailored strategy for each patient. It is essential to optimize every aspect of the treatment plan to set the CAR T cells and the patient up for success,” says Naik.

Celebrating the role of team-science in improving CAR T–cell therapy outcomes

The growth of the CAR T–cell therapy program at St. Jude is a testament not only to the strength of a team-science approach, but also to its people. The team has done well by all measurable metrics of growth, just as Alfonso has, and is continuing to evolve by launching a new Center of Excellence in pediatric immuno-oncology and recruiting new faculty.

While Alfonso experienced remission after his CAR T–cell therapy, he showed early indications of the CAR T cells disappearing, so he received a second bone-marrow transplant in February 2023.

In his last physical therapy appointment — having graduated and no longer in need of physical therapy — Alfonso follows the familiar footsteps on the St. Jude physical therapy floor.

Eighteen months later, and still in remission, three planes brought Alfonso and Monica from Mexico to Memphis for their latest checkup at St. Jude. In addition to his five-centimeter growth spurt, Alfonso graduated from physical therapy, another indicator of growth.

When he next returns to St. Jude, he will more than likely have to look down at his mother when he speaks to her, and he will undoubtedly be wearing a new pair of shoes, having long outgrown his current ones.

Special thanks: Interviews for this article were supported by the Spanish interpreter professionals in the Department of Interpreter Services at St. Jude.